Food marketing to children in school: Reading, writing, and a candy ad?

Food marketing to children works. Parents know from experience that food ads and marketing affect not only which foods their children ask them to purchase, but also which foods their kids are willing to eat.

- According to a comprehensive review by the National Academies’ Institute of Medicine, television food advertising affects children’s food choices, food purchase requests, diets, and health.1

- Studies also show that labeling and signage on school campuses affect students’ food selections at school.2

- The majority of public school students are exposed to some form of food and beverage marketing at school; in 2012, 70% of elementary and middle school students and 90% of high school students attended schools with food marketing.3

- In 2009, food companies spent $150 million marketing to children in school.4

Marketed foods typically are of poor nutritional quality. The overwhelming majority of foods marketed to children are of poor nutritional quality,5,6 including in schools.

- A national survey found that 67% of schools have advertising for foods that are high in fat and/or sugar.7

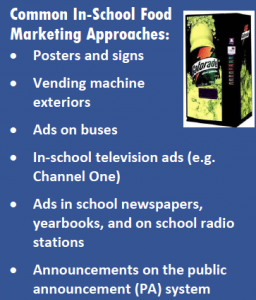

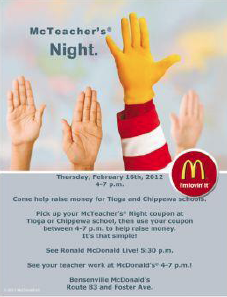

- Candy and snack food manufacturers, beverage companies, and fast-food restaurants are among the companies that market most heavily in schools.8,4

- In 2009, beverage companies accounted for more than 90% of marketing expenditures directed at children in schools.4

Marketing in schools undermines school food improvements. The 2010 Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act resulted in new USDA guidelines that are making school meals more wholesome and nutritious, and improving the nutritional quality of foods sold through vending, a la carte, school stores, fundraisers, and other foods outside of the school meal programs.9

- Yet companies can continue to market products that cannot be sold on campus, undermining the new USDA Smart Snack nutrition standards, healthy school meals, and students’ diets and health.

- Although some food and beverage companies have voluntarily agreed to limits on marketing in schools through the Children’s Food and Beverage Advertising Initiative (CFBAI), CFBAI’s school marketing guidelines exclude middle and high schools, and do not apply to many forms of marketing in elementary schools.10

Marketing of low-nutrition foods in schools undermines parents’ efforts to feed children a healthy diet, nutrition education efforts, and children’s health. While children are in school, parents are not there to help guide their children’s food choices.

- Only 20% of public school districts have a policy addressing food and beverage marketing, and only half of those districts explicitly prohibit the marketing of unhealthy food and beverages.11 Less than 10% of states have policies to limit unhealthy marketing in schools (AL, DC, ME, WV).

School Revenue. Districts typically receive minimal revenue, particularly compared to districts’ total budgets. A national study found that two-thirds of schools that engaged in commercial advertising received no income at all, and only 0.4% of schools generated more than $50,000.12

School Revenue. Districts typically receive minimal revenue, particularly compared to districts’ total budgets. A national study found that two-thirds of schools that engaged in commercial advertising received no income at all, and only 0.4% of schools generated more than $50,000.12

- Schools can still allow food and beverage marketing if they swap out unhealthy products for healthier ones (e.g. instead of featuring the Coca-Cola logo on a scoreboard, feature Diet Coke, or feature baked chips instead of regular chips on a school store display rack).

- There are many alternatives to unhealthy food marketing to raise revenue. School districts have had success with non-food fundraisers that are easy to implement and profitable, including selling fruit, jewelry, holiday items, and toys, walk-a-thons, discount cards, and recycling printer cartridges.13

Parents, the public, and school officials support limits on in-school marketing. In a national survey, 90% of the public reported that they oppose marketing of unhealthy food and soda in schools.14

Parents, the public, and school officials support limits on in-school marketing. In a national survey, 90% of the public reported that they oppose marketing of unhealthy food and soda in schools.14

- Seventy-seven percent of parents in a national poll said that they would prefer that companies directed their marketing toward them rather than at their children.15

- Sixty-nine percent of school officials participating in a national survey expressed strong support for increasing regulation of ads for low-nutrition foods in schools.15

For more information, please visit www.foodmarketing.org or contact Kate Klimczak: kklimczak@cspinet.org

References

1. Institute of Medicine. Food Marketing to Children: Threat or Opportunity? Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2006.

2. Hastings G. Does Food Promotion Influence Children? A Systematic Review of the Evidence. London, UK: Food Standards Agency, 2004.

3. Terry-McElrath Y, Turner L, Sandoval A, Johnston L, Chaloupka FJ. “Commercialism in US Elementary and Secondary School Nutrition Environments: Trends from 2007 to 2012. JAMA Pediatr. Doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.4521, 2014.

4. Federal Trade Commission. A Review of Food Marketing to Children and Adolescents: Follow-Up Report. Washington, DC: Federal Trade Commission, 2012.

5. Powell LM, Schermbeck RM, Chaloupka FJ. Nutritional content of food and beverage products in television advertisements seen on children’s programming. Child Obes. 2013 Nov 8.

6. Kunkel D. et al. The Impact of Industry Self-Regulation on the Nutritional Quality of Foods Advertised to Children on Television. Oakland, CA: Children Now, 2009.

7. Molnar A, Garcia DR, Boninger F, Merrill B. A National Survey of the Types and Extent of the Marketing of Foods of Minimal Nutritional Value in Schools. Tempe, AZ: Commercialism in Research Unit, 2006.

8. Center for Science in the Public Interest. Food and Beverage Marketing Survey: Montgomery County Public Schools. Washington, DC: Center for Science in the Public Interest, 2008. Available from: http://www.cspinet.org/nutritionpolicy/MCPS_foodmarketing_report2008.pdf

9. Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010. http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2013-06-28/pdf/2013-15249.pdf

10. Council of Better Business Bureaus, Inc. Children’s Food and Beverage Advertising Imitative Program and Core Principles Statement 4th Ed. Arlington, VA. Available: http://www.bbb.org/Global/Council_113/CFBAI/Enhanced%20Core%20Principles%20Fourth%20Edition%20with%20Appendix%20A.pdf

11. Chriqui JF, Resnick EA, Schneider L, Schermbeck R, Adcock T, Carrion V, Chaloupka FJ. School District Wellness Policies: Evaluating Progress and Potential for Improving Children’s Health Five Years after the Federal Mandate. Volume 3. Chicago, IL: Bridging the Gap Program, Health Policy Center, Institute for Health Research and Policy, University of Illinois at Chicago, 2013.

12. Molnar A, Garcia DR, Boninger F, Merrill B. A National Survey of the Types and Extent of the Marketing of Foods of Minimal Nutritional Value in Schools. Tempe, AZ: Commercialism in Research Unit, 2006.

13. Johnson J and Wootan M. Sweet Deals: School Fundraising Can Be Healthy and Profitable. Washington, DC: Center for Science in the Public Interest, 2007. Available: http://www.cspinet.org/schoolfundraising.pdf

14. Kasser T and Linn S. Public Attitudes Towards the Youth Marketing Industry and Its Impact on Children, 2004. Available: http://www.commercialfreechildhood.org/sites/default/files/kasser_publicattitudes.pdf

15. Prospectiv. Prospectiv Survey Reveals Parental Opinions and Preferences about Food Marketing to Children. February 15, 2006. Press statement. Available from: http://www.prospectiv.com/press62.jsp